Following a first trip to the country in 1968 that whetted his curiosity and a series of successive visits that unfolded all its splendours, Serge Lutens decided to purchase a house in Morocco in 1974. Perhaps he could rebuild a life for himself, far away from France? In recent years, the Artistic Director of Dior Beauty had admittedly been going through a dark phase in his personal life. The world thought of him as a man who had "carte blanche", with his successful make-up lines and advertising campaigns, but Serge felt that his position was still uncertain: every concept and every white-powdered woman that he put forth led to in-fighting within the brand between those that endorsed his radical approach and others that advocated more conventional forms of beauty. Lutens managed to have the final say despite these challenges, but he paid a heavy price for it!

Suffice it to say that he arrived in Marrakesh in a depressive state, a city he stumbled into, but would go on to win his heart. During that trip, I visited a countless number of houses, I don't even remember how many. Maybe three or four every day for a whole month! Then, just three days before my departure, an old man took me by the arm, and pulled me along, saying: "Come, I know just what you are looking for."

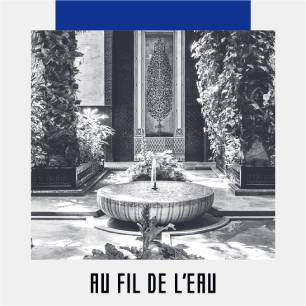

And the old man was right, for Serge Lutens was blown away by what he saw. Nestled in the heart of the Medina, the dilapidated house he set eyes on was utterly charming. Snakes glided in and out of the cypress trees that stood imposingly in the patio. The house was completely abandoned, but Serge seemed undaunted at the idea of its restoration. He saw parallels between the rebuilding of the house and his own self, and the two processes became inextricably intertwined.

Lutens got straight to work on the house, which he hoped to live in. The sounds of picks, hammers and chisels assaulted his senses every day, but rather than annoying him, they filled him with joy. His dream project was coming along! Serge Lutens painstakingly put together a mountain of archival documentation on medieval Moorish architecture as well as 20th-century Moroccan colonial styles to restore each section of the house. Calling on the expertise of traditional craftsmen called maalems, recruited locally from Marrakesh, Meknes and Fez, the Frenchman soon reinvented this past in a way that would surpass all his research. Wells, granaries and galleries buried hundreds of metres under the ground were unearthed. More than 500 workers toiled away at the site.

The house became a real maze, but paradoxically, Lutens began to feel less and less at home. The story he was writing in stone, lime and wood in the heart of the old city of Marrakesh was beginning to seep into his bones. He was chasing an ideal which had now taken over him completely. He was under its thumb. The house possessed and haunted him. Nothing was too beautiful or grand for it.

After obsessing over the wooden structure of the house, Serge Lutens then got down to designing each room and each piece of furniture. He got this furniture custom-made by local craftsmen, and it is quite common, even years later, to find replicas of these objects in the souk. Over the years, he went on to acquire 20 adjoining nobleman's homes, or riads, as Westerners call them. Almost like a living organism, the resulting labyrinthine complex now spreads out its corridors over 5000 sq.m. Yet, Serge Lutens relentlessly pursued his quest for the impossible. The closer his house got to perfection, the more assiduously he looked for the little flaws.

Inside, the air is filled with the scents emanating from the sculpted cedarwood ceilings, the jasmine trees in the lush courtyard and the old books in the library, which lend a mystical atmosphere to the space. The perfume of a life well-lived! For decades on end, Serge Lutens – who had exiled himself to a small hideout a few kilometres away from the city – guarded this house in the Medina away from the eyes of the world. Apart from some locals, nobody in his entourage had ever set foot in the home, reinforcing its mythical status. In the taxis of the city and among the merchants at the souk, tongues wagged: the story went that a man had constructed "the most beautiful house in the world", right in the heart of the Medina. Until one day, Serge Lutens decided to throw open the doors to this mansion, and the reality far surpassed everybody's expectations...

1°) Serge Lutens, I don't know if I should ask you why you kept this house away from prying eyes for so many years, or rather ask you why you've now decided to convert it into a Foundation and open it to private visits (as we know, the House can only be visited through an exclusive partnership with the Royal Mansour hotel)?

(06 :05) Well, simply because they came to me with the offer. They suggested it, otherwise I would have kept the house a secret. I would have left it as it is, closed to the outside world, because I would have kept saying to myself: "It's not perfect yet, so I can't open it. It's not good enough, it's not this or that or the other." And well, you know, it all goes back to my childhood. I was born in 1942, at a time when the anti-adultery laws of the Vichy regime were in full force. And even though I was the natural son of my father, he didn't recognize me until I was 3 years old. So, I was a child of unknown paternity for a while, and that, as well as my mother's guilt, was quite a heavy cross to bear, if you see what I mean. Her mistake became my mistake. I am the living incarnation of this mistake, and in a way, I have spent my whole life both prolonging it and trying to fix it at once. To me it's like the two sides of a knitting pattern. That's how I would put it, really, one stitch on the front side and then one on the back, the garter stitch, or whatever it's called. (07 :23) Yes, that's what it's like. Something like that.

So, you know, all this pursuit of perfection, this quest of beauty for beauty's sake, it all boils down to that instinct. I have worked with many gifted artisans and met wonderful people, and I have learned from them too. I showed them books, objects, things that I discovered in the national library during my research, because I wanted the best, most beautiful result. I am someone who plunders and restores at the same time. I think that's the fundamental principle behind my work. You know, there is this French artist called Reynaud who once built a house, and before doing so, he said: "I need to get rid of my life before beginning this house. " So, he got divorced. He had children and a wife whom he left and cut ties with...he made a clean break with his previous life. Then he built a house using the white tiles used in the Parisian metro at the time, so they were completely colourless, which incidentally I find more beautiful and joyful than all the horrible colours we now find lining the walls of the underground. He made it a kind of bunker, like a kind of shelter...it was a rejection, a fear even, of the ideal world. (08 :47) And he closed off this house, even going to the extent of putting barbed wire around it, and installing a watchtower. His intention was so clear: he wanted to push this house to the limits of solitude. And then, he went about decorating it. Which is to say that he put in beautiful textiles, plants that could live without light – because of course the house was completely sealed off – carnivorous or poisonous plants.

Moroccan houses appeal to me because they too are closed off from the outside, but open on the inside. In fact, the exterior of these houses tends to be quite unadorned. Even the most luxurious houses are modest on the outside. It is hard to tell from the outside what they are like on the inside, because they are so completely woven into the social fabric. I've come back to my knitting metaphor, you see. As for opening it, well, it just wasn't finished. I wanted it to be beautiful. I needed it to be very beautiful. But in the end, if the offer hadn't been made to me, I would have never opened it because it would never have been beautiful enough. Because the ideal beauty doesn't exist. One can only seek it, almost like a religious pursuit. It is a kind of asceticism. Something to which one submits. And do you know what Raynaud did after building his house? He razed it to the ground, demolishing it first with a hammer then with a bulldozer. He tore it down and then put the fragments in small aluminium buckets which were then put on display in Venice. It was incredible. Quite extraordinary, and I quite understand why he did it. He wanted to pursue something to its end. And when the end arrives, well, there is nothing left to say about it. One must begin anew, start something else. That is the way of life, the cycle of life and death.

2°) In the past, you have said that this house is the "redressal of a mistake." What did you mean by that?

(10 :41) It's as I've just explained it, you know, it was like fixing this mistake, a mistake that is not even my own really. In fact, I only learned about all this when I was much older, I didn't know about it at all as a child, despite being separated from my mother. I knew there was something wrong... But I didn't understand why I was being carted from one family into another, and why people came to visit me in secret, in hiding. There was nothing dramatic or tragic about it. It's just something that happened to me, in my life. Everyone has their own life story and background. And everyone has something they have to go through. But in my case, this mistake, which comes from love, is something I’ve tried to repair. I am a man with a lot of anger, it's quite a strong emotion for me. Creation without anger is not possible. It simply doesn't exist. Creation is not a bed of roses. No. That would be lethally boring.

3°) One can see then that the house stopped being a living space to which only you had access. A bit like the white women that appeared in the Dior and Shiseido ad campaigns. How do you feel about it and what is your relationship with it like now?

(11 :59) One's relationship to beauty never changes. I will keep saying the same thing to you throughout this interview, I think. I will keep talking about this mistake, because I feel it is important to go back to the root of it all. Everything happens before you turn seven. The seven-year birthday marks the entry into the age of reason. Everything is determined at that age, who we are and what we are going to be. This is true, not just for me, but for you and for every human being alive. In short, that's the kernel of everything, that's what it all comes down to. Nothing else matters. The first seven years of your life decide whether you as an adult will be a monster, a lover, a lost soul, a suicidal person, a tightrope walker or famous dancer, whatever it is. One's whole life is interesting, but one can only attribute those events to childhood, if you see what I mean.

Some people manage to escape this fate and fit into the moulds of conventional society. I recently watched a short film on Nureyev, who came from the poorest sections of Communist Russia at a terrible time, and how he came to...I've seen him dancing at the Louvre, in the courtyard, Nureyev, and he was a delight. He had wings in his feet and legs. He had absorbed and learnt so much from female dancers, you know, creativity is feminine for a man, and masculine for a woman. And God, who is the giver of everything, is feminine. He creates the feminine, and manifests through the feminine. That's what I mean.

4°) Several magazines have dedicated articles to your house, which is often referred to as a piece of art in its own right, a significant oeuvre in your work. What do you think about that?

(13 :50) I don't like using words like "oeuvre," because I think that it's more a matter of "manoeuvre", actually. In one sense you could call it an "oeuvre", if you like, because I met these artisans and I gave them something and they gave me something in return. One doesn't build something like that alone. It's a collection of things, a kind of machine that gets set in motion. Yes, it's a machine more than anything else.

5°) Many have begun wondering about the fate of the Foundation after your passing? Do you have any vision for its legacy?

(14 :30) No. Because I don't care. Because in the end, it ends with me. Period. My world ends when I go. Period. Just like my world starts with my birth, and this is true for everyone. As to what happens to things after us, well...one is happy to let go of them, but also sad at the same time, because things will happen, and life will go on. I mean, what one person creates is then carried on by others. A caress. A smile. An approach, a gesture. All these lead to other things in a continuing cycle. They weave into each other, if you will forgive me coming back to the knitting metaphor. It's like a dance. We learn the steps but then they are danced by others. Or we create the steps, and they are still danced by others. In either case, we don't know what will happen.

Also, the future doesn't interest me, for I don't know what it means. And in any case, that's not the point, you know. Anything that comes after me will be derivative, something that comes from me but no longer belongs to me. A kind of caricature. Like when a writer who's gone; we can put on one mask or another to make them look the way we see them. I don't need to go on, because I think you get what I'm saying. After one is gone, one becomes a kind of entity, a type of monster, because the human being has ceased to exist. But they have left something behind, which will necessarily turn into a pastiche.

That's not what I am here for, or why I do what I do. I need to create to be alive. What will happen in the future, well I have many projects, too many, in fact. I need to zero in on only one thing, that's the problem. Turning it into a foundation was a way of engaging, if you will. Generosity is a complex thing. Where does generosity begin, how can one be generous without it being colonial, without having this "colonizing" effect, because of course it will help a lot of people but it will also kill others. These questions are interesting. Even the worst encounters can be interesting, because they have so much to teach us.